How to choose the right concurrency model

Python provides three main approaches to handle multiple tasks simultaneously: multithreading, multiprocessing, and asyncio.

Choosing the right model is crucial for maximising your program’s performance and efficiently using system resources. (P.S. It is also a common interview question!)

Without concurrency, a program processes only one task at a time. During operations like file loading, network requests, or user input, it stays idle, wasting valuable CPU cycles. Concurrency solves this by enabling multiple tasks to run efficiently.

But which model should you use? Let’s dive in!

Contents

- Fundamentals of concurrency

– Concurrency vs parallelism

– Programs

– Processes

– Threads

– How does the OS manage threads and processes? - Python’s concurrency models

– Multithreading

– Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

– Multiprocessing

– Asyncio - When should I use which concurrency model?

Fundamentals of concurrency

Before jumping into Python’s concurrency models, let’s recap some foundational concepts.

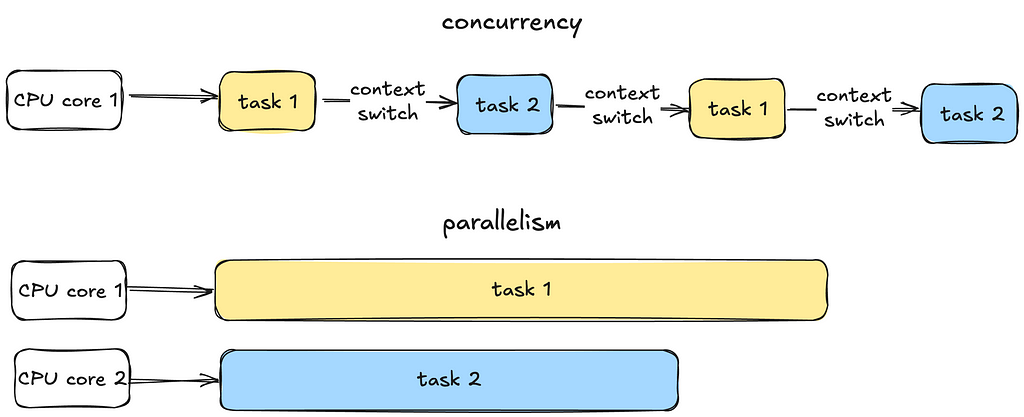

1. Concurrency vs Parallelism

Concurrency is all about managing multiple tasks at the same time, not necessarily simultaneously. Tasks may take turns, creating the illusion of multitasking.

Parallelism is about running multiple tasks simultaneously, typically by leveraging multiple CPU cores.

2. Programs

Now let’s move on to some fundamental OS concepts — programs, processes and threads.

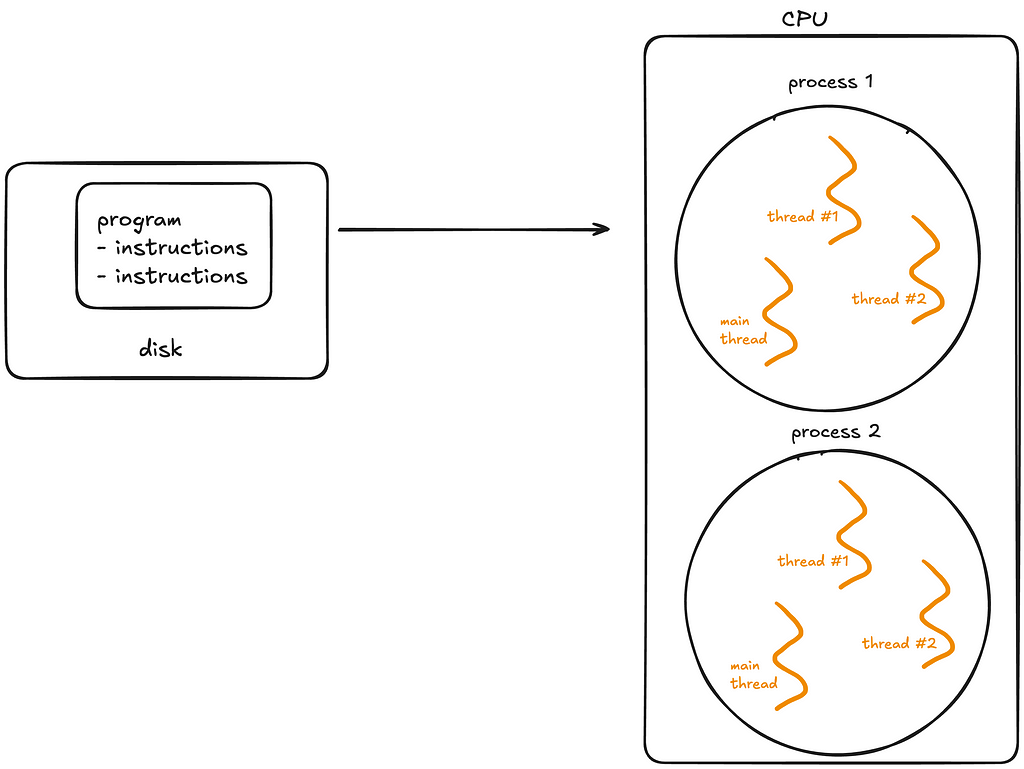

A program is simply a static file, like a Python script or an executable.

A program sits on disk, and is passive until the operating system (OS) loads it into memory to run. Once this happens, the program becomes a process.

3. Processes

A process is an independent instance of a running program.

A process has its own memory space, resources, and execution state. Processes are isolated from each other, meaning one process cannot interfere with another unless explicitly designed to do so via mechanisms like inter-process communication (IPC).

Processes can generally be categorised into two types:

- I/O-bound processes:

Spend most of it’s time waiting for input/output operations to complete, such as file access, network communication, or user input. While waiting, the CPU sits idle. - CPU-bound processes:

Spend most of their time doing computations (e.g video encoding, numerical analysis). These tasks require a lot of CPU time.

Lifecycle of a process:

- A process starts in a new state when created.

- It moves to the ready state, waiting for CPU time.

- If the process waits for an event like I/O, it enters the waiting state.

- Finally, it terminates after completing its task.

4. Threads

A thread is the smallest unit of execution within a process.

A process acts as a “container” for threads, and multiple threads can be created and destroyed over the process’s lifetime.

Every process has at least one thread — the main thread — but it can also create additional threads.

Threads share memory and resources within the same process, enabling efficient communication. However, this sharing can lead to synchronisation issues like race conditions or deadlocks if not managed carefully. Unlike processes, multiple threads in a single process are not isolated — one misbehaving thread can crash the entire process.

5. How does the OS manage threads and processes?

The CPU can execute only one task per core at a time. To handle multiple tasks, the operating system uses preemptive context switching.

During a context switch, the OS pauses the current task, saves its state and loads the state of the next task to be executed.

This rapid switching creates the illusion of simultaneous execution on a single CPU core.

For processes, context switching is more resource-intensive because the OS must save and load separate memory spaces. For threads, switching is faster because threads share the same memory within a process. However, frequent switching introduces overhead, which can slow down performance.

True parallel execution of processes can only occur if there are multiple CPU cores available. Each core handles a separate process simultaneously.

Python’s concurrency models

Let’s now explore Python’s specific concurrency models.

1. Multithreading

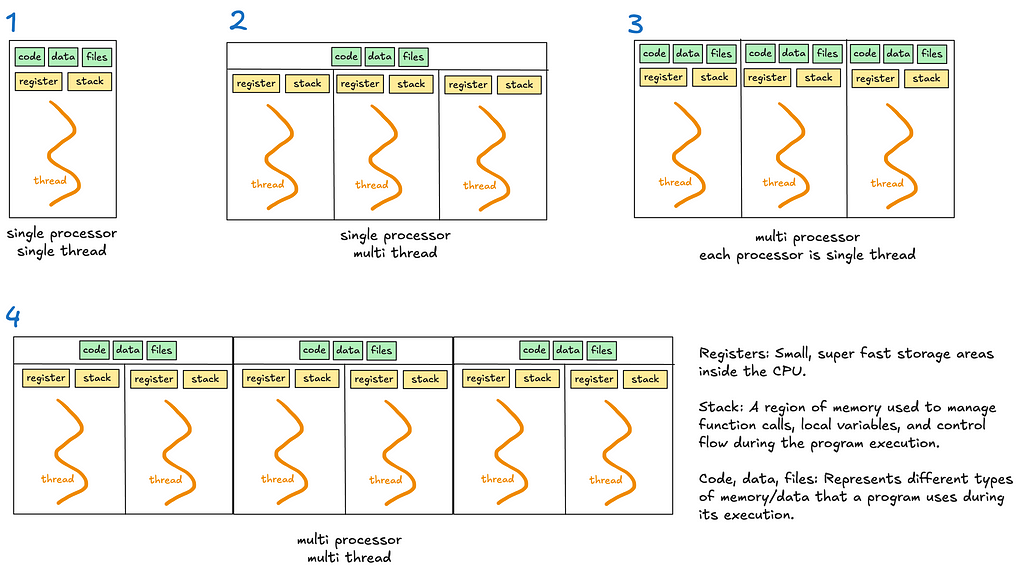

Multithreading allows a process to execute multiple threads concurrently, with threads sharing the same memory and resources (see diagrams 2 and 4).

However, Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) limits multithreading’s effectiveness for CPU-bound tasks.

Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)

The GIL is a lock that allows only one thread to hold control of the Python interpreter at any time, meaning only one thread can execute Python bytecode at once.

The GIL was introduced to simplify memory management in Python as many internal operations, such as object creation, are not thread safe by default. Without a GIL, multiple threads trying to access the shared resources will require complex locks or synchronisation mechanisms to prevent race conditions and data corruption.

When is GIL a bottleneck?

- For single threaded programs, the GIL is irrelevant as the thread has exclusive access to the Python interpreter.

- For multithreaded I/O-bound programs, the GIL is less problematic as threads release the GIL when waiting for I/O operations.

- For multithreaded CPU-bound operations, the GIL becomes a significant bottleneck. Multiple threads competing for the GIL must take turns executing Python bytecode.

An interesting case worth noting is the use of time.sleep, which Python effectively treats as an I/O operation. The time.sleep function is not CPU-bound because it does not involve active computation or the execution of Python bytecode during the sleep period. Instead, the responsibility of tracking the elapsed time is delegated to the OS. During this time, the thread releases the GIL, allowing other threads to run and utilise the interpreter.

2. Multiprocessing

Multiprocessing enables a system to run multiple processes in parallel, each with its own memory, GIL and resources. Within each process, there may be one or more threads (see diagrams 3 and 4).

Multiprocessing bypasses the limitations of the GIL. This makes it suitable for CPU bound tasks that require heavy computation.

However, multiprocessing is more resource intensive due to separate memory and process overheads.

3. Asyncio

Unlike threads or processes, asyncio uses a single thread to handle multiple tasks.

When writing asynchronous code with the asyncio library, you’ll use the async/await keywords to manage tasks.

Key concepts

- Coroutines: These are functions defined with async def . They are the core of asyncio and represent tasks that can be paused and resumed later.

- Event loop: It manages the execution of tasks.

- Tasks: Wrappers around coroutines. When you want a coroutine to actually start running, you turn it into a task — eg. using asyncio.create_task()

- await : Pauses execution of a coroutine, giving control back to the event loop.

How it works

Asyncio runs an event loop that schedules tasks. Tasks voluntarily “pause” themselves when waiting for something, like a network response or a file read. While the task is paused, the event loop switches to another task, ensuring no time is wasted waiting.

This makes asyncio ideal for scenarios involving many small tasks that spend a lot of time waiting, such as handling thousands of web requests or managing database queries. Since everything runs on a single thread, asyncio avoids the overhead and complexity of thread switching.

The key difference between asyncio and multithreading lies in how they handle waiting tasks.

- Multithreading relies on the OS to switch between threads when one thread is waiting (preemptive context switching).

When a thread is waiting, the OS switches to another thread automatically. - Asyncio uses a single thread and depends on tasks to “cooperate” by pausing when they need to wait (cooperative multitasking).

2 ways to write async code:

method 1: await coroutine

When you directly await a coroutine, the execution of the current coroutine pauses at the await statement until the awaited coroutine finishes. Tasks are executed sequentially within the current coroutine.

Use this approach when you need the result of the coroutine immediately to proceed with the next steps.

Although this might sound like synchronous code, it’s not. In synchronous code, the entire program would block during a pause.

With asyncio, only the current coroutine pauses, while the rest of the program can continue running. This makes asyncio non-blocking at the program level.

Example:

The event loop pauses the current coroutine until fetch_data is complete.

async def fetch_data():

print("Fetching data...")

await asyncio.sleep(1) # Simulate a network call

print("Data fetched")

return "data"

async def main():

result = await fetch_data() # Current coroutine pauses here

print(f"Result: {result}")

asyncio.run(main())

method 2: asyncio.create_task(coroutine)

The coroutine is scheduled to run concurrently in the background. Unlike await, the current coroutine continues executing immediately without waiting for the scheduled task to finish.

The scheduled coroutine starts running as soon as the event loop finds an opportunity, without needing to wait for an explicit await.

No new threads are created; instead, the coroutine runs within the same thread as the event loop, which manages when each task gets execution time.

This approach enables concurrency within the program, allowing multiple tasks to overlap their execution efficiently. You will later need to await the task to get it’s result and ensure it’s done.

Use this approach when you want to run tasks concurrently and don’t need the results immediately.

Example:

When the line asyncio.create_task() is reached, the coroutine fetch_data() is scheduled to start running immediately when the event loop is available. This can happen even before you explicitly await the task. In contrast, in the first await method, the coroutine only starts executing when the await statement is reached.

Overall, this makes the program more efficient by overlapping the execution of multiple tasks.

async def fetch_data():

# Simulate a network call

await asyncio.sleep(1)

return "data"

async def main():

# Schedule fetch_data

task = asyncio.create_task(fetch_data())

# Simulate doing other work

await asyncio.sleep(5)

# Now, await task to get the result

result = await task

print(result)

asyncio.run(main())

Other important points

- You can mix synchronous and asynchronous code.

Since synchronous code is blocking, it can be offloaded to a separate thread using asyncio.to_thread(). This makes your program effectively multithreaded.

In the example below, the asyncio event loop runs on the main thread, while a separate background thread is used to execute the sync_task.

import asyncio

import time

def sync_task():

time.sleep(2)

return "Completed"

async def main():

result = await asyncio.to_thread(sync_task)

print(result)

asyncio.run(main())

- You should offload CPU-bound tasks which are computationally intensive to a separate process.

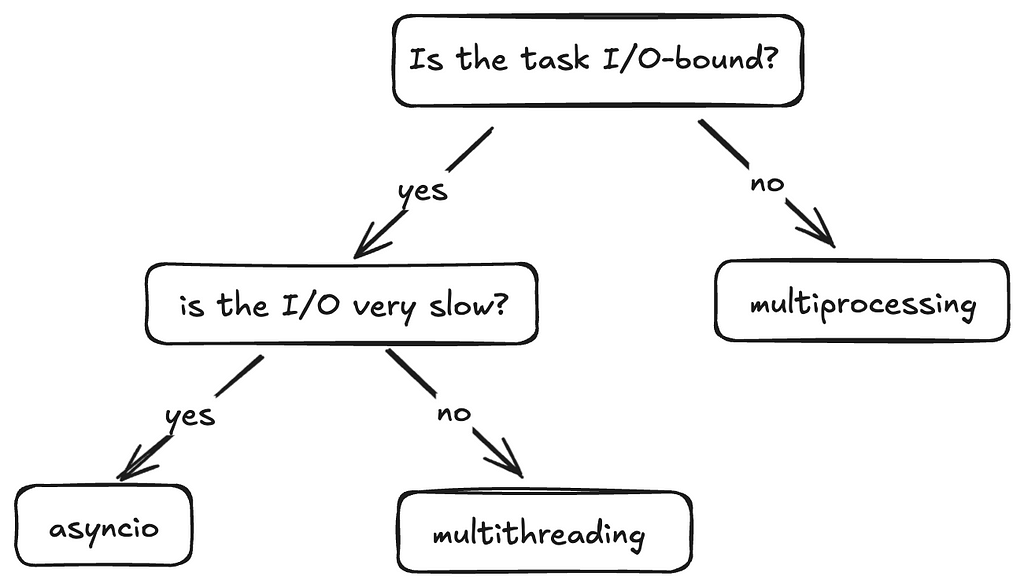

When should I use which concurrency model?

This flow is a good way to decide when to use what.

- Multiprocessing

– Best for CPU-bound tasks which are computationally intensive.

– When you need to bypass the GIL — Each process has it’s own Python interpreter, allowing for true parallelism. - Multithreading

– Best for fast I/O-bound tasks as the frequency of context switching is reduced and the Python interpreter sticks to a single thread for longer

– Not ideal for CPU-bound tasks due to GIL. - Asyncio

– Ideal for slow I/O-bound tasks such as long network requests or database queries because it efficiently handles waiting, making it scalable.

– Not suitable for CPU-bound tasks without offloading work to other processes.

Wrapping up

That’s it folks. There’s a lot more that this topic has to cover but I hope I’ve introduced to you the various concepts, and when to use each method.

Thanks for reading! I write regularly on Python, software development and the projects I build, so give me a follow to not miss out. See you in the next article 🙂

Deep Dive into Multithreading, Multiprocessing, and Asyncio was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

How to choose the right concurrency modelImage by Paul Esch-Laurent from UnsplashPython provides three main approaches to handle multiple tasks simultaneously: multithreading, multiprocessing, and asyncio.Choosing the right model is crucial for maximising your program’s performance and efficiently using system resources. (P.S. It is also a common interview question!)Without concurrency, a program processes only one task at a time. During operations like file loading, network requests, or user input, it stays idle, wasting valuable CPU cycles. Concurrency solves this by enabling multiple tasks to run efficiently.But which model should you use? Let’s dive in!ContentsFundamentals of concurrency- Concurrency vs parallelism- Programs- Processes- Threads- How does the OS manage threads and processes?Python’s concurrency models- Multithreading- Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)- Multiprocessing- AsyncioWhen should I use which concurrency model?Fundamentals of concurrencyBefore jumping into Python’s concurrency models, let’s recap some foundational concepts.1. Concurrency vs ParallelismVisual representation of concurrency vs parallelism (drawn by me)Concurrency is all about managing multiple tasks at the same time, not necessarily simultaneously. Tasks may take turns, creating the illusion of multitasking.Parallelism is about running multiple tasks simultaneously, typically by leveraging multiple CPU cores.2. ProgramsNow let’s move on to some fundamental OS concepts — programs, processes and threads.Multiple threads can exist simultaneously within the a single process — known as multithreading (drawn by me)A program is simply a static file, like a Python script or an executable.A program sits on disk, and is passive until the operating system (OS) loads it into memory to run. Once this happens, the program becomes a process.3. ProcessesA process is an independent instance of a running program.A process has its own memory space, resources, and execution state. Processes are isolated from each other, meaning one process cannot interfere with another unless explicitly designed to do so via mechanisms like inter-process communication (IPC).Processes can generally be categorised into two types:I/O-bound processes:Spend most of it’s time waiting for input/output operations to complete, such as file access, network communication, or user input. While waiting, the CPU sits idle.CPU-bound processes:Spend most of their time doing computations (e.g video encoding, numerical analysis). These tasks require a lot of CPU time.Lifecycle of a process:A process starts in a new state when created.It moves to the ready state, waiting for CPU time.If the process waits for an event like I/O, it enters the waiting state.Finally, it terminates after completing its task.4. ThreadsA thread is the smallest unit of execution within a process.A process acts as a “container” for threads, and multiple threads can be created and destroyed over the process’s lifetime.Every process has at least one thread — the main thread — but it can also create additional threads.Threads share memory and resources within the same process, enabling efficient communication. However, this sharing can lead to synchronisation issues like race conditions or deadlocks if not managed carefully. Unlike processes, multiple threads in a single process are not isolated — one misbehaving thread can crash the entire process.5. How does the OS manage threads and processes?The CPU can execute only one task per core at a time. To handle multiple tasks, the operating system uses preemptive context switching.During a context switch, the OS pauses the current task, saves its state and loads the state of the next task to be executed.This rapid switching creates the illusion of simultaneous execution on a single CPU core.For processes, context switching is more resource-intensive because the OS must save and load separate memory spaces. For threads, switching is faster because threads share the same memory within a process. However, frequent switching introduces overhead, which can slow down performance.True parallel execution of processes can only occur if there are multiple CPU cores available. Each core handles a separate process simultaneously.Python’s concurrency modelsLet’s now explore Python’s specific concurrency models.Summary of the different concurrency models (drawn by me)1. MultithreadingMultithreading allows a process to execute multiple threads concurrently, with threads sharing the same memory and resources (see diagrams 2 and 4).However, Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL) limits multithreading’s effectiveness for CPU-bound tasks.Python’s Global Interpreter Lock (GIL)The GIL is a lock that allows only one thread to hold control of the Python interpreter at any time, meaning only one thread can execute Python bytecode at once.The GIL was introduced to simplify memory management in Python as many internal operations, such as object creation, are not thread safe by default. Without a GIL, multiple threads trying to access the shared resources will require complex locks or synchronisation mechanisms to prevent race conditions and data corruption.When is GIL a bottleneck?For single threaded programs, the GIL is irrelevant as the thread has exclusive access to the Python interpreter.For multithreaded I/O-bound programs, the GIL is less problematic as threads release the GIL when waiting for I/O operations.For multithreaded CPU-bound operations, the GIL becomes a significant bottleneck. Multiple threads competing for the GIL must take turns executing Python bytecode.An interesting case worth noting is the use of time.sleep, which Python effectively treats as an I/O operation. The time.sleep function is not CPU-bound because it does not involve active computation or the execution of Python bytecode during the sleep period. Instead, the responsibility of tracking the elapsed time is delegated to the OS. During this time, the thread releases the GIL, allowing other threads to run and utilise the interpreter.2. MultiprocessingMultiprocessing enables a system to run multiple processes in parallel, each with its own memory, GIL and resources. Within each process, there may be one or more threads (see diagrams 3 and 4).Multiprocessing bypasses the limitations of the GIL. This makes it suitable for CPU bound tasks that require heavy computation.However, multiprocessing is more resource intensive due to separate memory and process overheads.3. AsyncioUnlike threads or processes, asyncio uses a single thread to handle multiple tasks.When writing asynchronous code with the asyncio library, you’ll use the async/await keywords to manage tasks.Key conceptsCoroutines: These are functions defined with async def . They are the core of asyncio and represent tasks that can be paused and resumed later.Event loop: It manages the execution of tasks.Tasks: Wrappers around coroutines. When you want a coroutine to actually start running, you turn it into a task — eg. using asyncio.create_task()await : Pauses execution of a coroutine, giving control back to the event loop.How it worksAsyncio runs an event loop that schedules tasks. Tasks voluntarily “pause” themselves when waiting for something, like a network response or a file read. While the task is paused, the event loop switches to another task, ensuring no time is wasted waiting.This makes asyncio ideal for scenarios involving many small tasks that spend a lot of time waiting, such as handling thousands of web requests or managing database queries. Since everything runs on a single thread, asyncio avoids the overhead and complexity of thread switching.The key difference between asyncio and multithreading lies in how they handle waiting tasks.Multithreading relies on the OS to switch between threads when one thread is waiting (preemptive context switching).When a thread is waiting, the OS switches to another thread automatically.Asyncio uses a single thread and depends on tasks to “cooperate” by pausing when they need to wait (cooperative multitasking).2 ways to write async code:method 1: await coroutineWhen you directly await a coroutine, the execution of the current coroutine pauses at the await statement until the awaited coroutine finishes. Tasks are executed sequentially within the current coroutine.Use this approach when you need the result of the coroutine immediately to proceed with the next steps.Although this might sound like synchronous code, it’s not. In synchronous code, the entire program would block during a pause.With asyncio, only the current coroutine pauses, while the rest of the program can continue running. This makes asyncio non-blocking at the program level.Example:The event loop pauses the current coroutine until fetch_data is complete.async def fetch_data(): print(“Fetching data…”) await asyncio.sleep(1) # Simulate a network call print(“Data fetched”) return “data”async def main(): result = await fetch_data() # Current coroutine pauses here print(f”Result: {result}”)asyncio.run(main())method 2: asyncio.create_task(coroutine)The coroutine is scheduled to run concurrently in the background. Unlike await, the current coroutine continues executing immediately without waiting for the scheduled task to finish.The scheduled coroutine starts running as soon as the event loop finds an opportunity, without needing to wait for an explicit await.No new threads are created; instead, the coroutine runs within the same thread as the event loop, which manages when each task gets execution time.This approach enables concurrency within the program, allowing multiple tasks to overlap their execution efficiently. You will later need to await the task to get it’s result and ensure it’s done.Use this approach when you want to run tasks concurrently and don’t need the results immediately.Example:When the line asyncio.create_task() is reached, the coroutine fetch_data() is scheduled to start running immediately when the event loop is available. This can happen even before you explicitly await the task. In contrast, in the first await method, the coroutine only starts executing when the await statement is reached.Overall, this makes the program more efficient by overlapping the execution of multiple tasks.async def fetch_data(): # Simulate a network call await asyncio.sleep(1) return “data”async def main(): # Schedule fetch_data task = asyncio.create_task(fetch_data()) # Simulate doing other work await asyncio.sleep(5) # Now, await task to get the result result = await task print(result)asyncio.run(main())Other important pointsYou can mix synchronous and asynchronous code. Since synchronous code is blocking, it can be offloaded to a separate thread using asyncio.to_thread(). This makes your program effectively multithreaded.In the example below, the asyncio event loop runs on the main thread, while a separate background thread is used to execute the sync_task.import asyncioimport timedef sync_task(): time.sleep(2) return “Completed”async def main(): result = await asyncio.to_thread(sync_task) print(result)asyncio.run(main())You should offload CPU-bound tasks which are computationally intensive to a separate process.When should I use which concurrency model?This flow is a good way to decide when to use what.Flowchart (drawn by me), referencing this stackoverflow discussionMultiprocessing- Best for CPU-bound tasks which are computationally intensive.- When you need to bypass the GIL — Each process has it’s own Python interpreter, allowing for true parallelism.Multithreading- Best for fast I/O-bound tasks as the frequency of context switching is reduced and the Python interpreter sticks to a single thread for longer- Not ideal for CPU-bound tasks due to GIL.Asyncio- Ideal for slow I/O-bound tasks such as long network requests or database queries because it efficiently handles waiting, making it scalable. – Not suitable for CPU-bound tasks without offloading work to other processes.Wrapping upThat’s it folks. There’s a lot more that this topic has to cover but I hope I’ve introduced to you the various concepts, and when to use each method.Thanks for reading! I write regularly on Python, software development and the projects I build, so give me a follow to not miss out. See you in the next article :)Deep Dive into Multithreading, Multiprocessing, and Asyncio was originally published in Towards Data Science on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story. concurrency, python, asynchronous, multiprocessing, multithreading Towards Data Science – MediumRead More

Add to favorites

Add to favorites

0 Comments